With Dementia we often think of memory complaints, one of the most important signals that can indicate Alzheimer’s disease. There are, however, a number of common forms of Dementia that sometimes show very different symptoms, such as Vascular Dementia, Lewy Body Dementia or Dementia due to Parkinson’s disease. Dementia affects the brain, and the brain is what controls our behaviors. As a result, not only our memory and way of thinking are affected, but also our behaviors and emotions.

Behavior

Problem behavior with Dementia can be defined in many different ways. A commonly used definition is that problem behavior is all behavior of a person or patient who is experienced as difficult to handle, by himself and/or his environment that sustains the behavior. This definition reflects on the fact that behavior can be a problem for a person, a patient or his environment.

With Dementia it’s likely to talk about changing behavior.

Many people with Dementia do experience changing behaviors. Studies indicate that anywhere from 60% to 90% of people with Dementia develop behavior concerns at some point in their disease.

How does changing behavior arise?

As I said before problems with changing behavior can have many causes. Which can be directly related to the disease, and also with the environment in which someone lives or is cared for.

With the person

- Side effects of medicines

- An additional disease that causes pain, which Dementia cannot make clear

- Poor vision or poor hearing, and no tools that compensate for this

- Frustration because he or she can handle less than before

- Anxiety through hallucinations or delusions

- Frustration because he or she notices that they are losing grip on their life

- Gloom because of the feeling that something is no longer possible.

There are some people who remain “pleasantly confused” the whole time they have Dementia. For some reason, these people don’t become anxious or agitated.

In the area

- Too many incentives (for example a lot of visitors, loud noises)

- Too little room to move (people with dementia can have a strong urge to move)

- No meaningful use of time (daytime activities, hobbies)

- Too much interest and good intentions from others

- Too little professional support or too many different people who provide care.

Many times, we can put our detective skills to use and figure out a cause for the behavior, and then that helps us determine how we should respond and try to prevent it.

Some common changes in behavior to observe

Movement Unrest

A person suffering from Dementia can be restless. He wanders aimlessly, drums with his fingers, shuffles with his feet, opens and closes drawers randomly, or pacing up and down the house.

Aggressive behavior

Someone with Dementia can display aggressive behavior, such as swearing, threatening and beating. If someone is anxious, he or she can respond with aggressive behavior because he or she can no longer express himself in the usual way.

Aggressive behavior can occur if he or she panics, for example during physical care. They are ashamed, afraid or frustrated that they can no longer wash their self.

Irritability

People with Dementia can be irritable or irritated under different circumstances. The irritation often focuses on the person who is most involved. Because that person is simply around, or because the person with dementia feels that he is becoming increasingly dependent on this person.

Uninhibited behavior

Impulsive and inappropriate behavior, also known as inhibition symptoms, are known behavioral problems. Someone with dementia can tell personal information to a complete stranger on the street or talk through a conversation in a loud tone. He may also exhibit inappropriate sexual behavior. He fails to notice that his attitude is not appropriate in a certain situation.

Mood problems

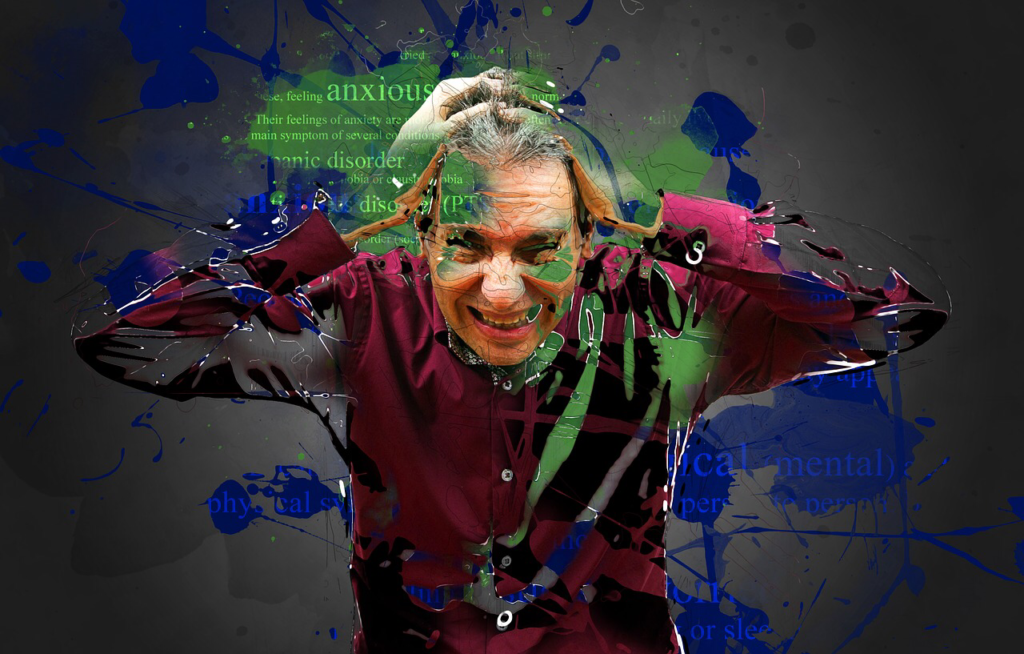

About 85% of people with Dementia suffer from mood problems: depression, anxiety, and apathy. Apathy is listlessness, indifference and the loss of initiative. They are less interested in the world around them, often don’t feel like doing anything and have flattened emotions. Someone who suffers from anxiety or suffers from depression is often gloomy, pessimistic and afraid to leave the house. If someone is anxious or in panic, they can react with aggressive behavior because they can no longer express themselves in the usual way.

Delusions and hallucinations

Sometimes people with Dementia develop psychotic problems such as delusions and hallucinations. The illusion is being robbed on a regular basis. He accuses family members of stealing lost things. Hallucinations also occur, for example seeing people or hearing sounds that are not there. These hallucinations can be frightening. Hallucinations can also be pleasant, for example when people see beautiful colors that are not actually there.

Personalities

Behavioral problems are usually not isolated but have to do with living conditions, problems with communication or frustration about the loss of independence.

Sometimes, Dementia seems to bring out the individual’s basic personality all the more. Other times, personalities seem to be completely different as Dementia progresses.

For example, a husband who has been faithful to his wife for their entire marriage may now be attempting to touch someone inappropriately or begin to have a “girlfriend” at a facility where he lives. Another person may have always been hospitable and welcoming, and now refuses to open the door to visitors and can be heard screaming for them to leave.

Family and caregivers can help reduce combative behavior

Don’t rush:

- Remember to give a little space to the person living with Dementia. When you invade someone’s personal space and they don’t understand why you can expect resistance or combativeness with care. Allow plenty of time when helping your loved one get ready for the day. Repeatedly telling him or her that it’s time to go and that he or she’s going to be late just increases their stress, anxiety, and frustration, which typically will decrease their ability to function well.

Talk before trying:

- Reminisce about something you know he or she is interested in before you attempt to physically care for the person. Take 3 minutes to establish a rapport with him by talking about his or her favorite sports team or job as a teacher. Three minutes upfront might save you 30 minutes. You might otherwise spend on trying to calm him down.

Use a visual cue:

- When you explain what you’re hoping to help her or him with, do show her or him with your own body. For example, if you want to help her brush their teeth, tell them that and make a gesture of brushing your own teeth with the toothbrush.

Take time out:

- If it’s not going well, ensure the safety of your family member or resident and come back in 15-20 minutes. A few minutes can sometimes seem like an entire day.

Switch caregivers:

- If you have the luxury of multiple caregivers, try having someone else approach the person with Dementia. Sometimes, the fresh face of a different caregiver can yield better results.

Less is more:

- Is what you’re trying to help with is really necessary? Then continue to work on it. If you can let something else go that’s not as important for the day, both you and your family member will benefit if you pick your battles.

Offer a familiar item to hold:

- Sometimes, a person can be reassured and calmed simply by holding a stuffed kitten, therapeutic baby doll or favorite photo album.

Don’t argue:

- It is never helpful to argue with someone who has Dementia. Use distraction or just listen.

Remain calm:

- Even though you might feel frustrated. Your family member will respond better if you stay calm and relaxed. If your tone becomes escalated and irritated, it’s very likely your loved one will, too. People who have Dementia often reflect back to their family members or caregivers the emotions that they see.

When you need more information or tips don’t hesitate to contact us for an acquaintance.